From artefacts to digital gems

By Dirk Rieke-Zapp, Senior Product Manager Structured Light and Photogrammetry, Hexagon’s Manufacturing Intelligence division

Engineering Reality 2024 volume 1

Accelerate Smart Manufacturing

Revolutionising the preservation and documentation of historical artefacts through a pioneering partnership and cutting-edge scanning technology

LfAS has been in its current legal form since 1993, but its origins can be traced back to the 1950s as the State Museum for Prehistory. Over the years, it has grown into a substantial organisation, boasting a team of approximately 80 permanent employees. When factoring in project staff involved in excavations, the total workforce can reach around 300 individuals. One of the remarkable aspects of the office is its extensive storage, housing over 20 million archaeological finds. This impressive collection establishes LfAS as a significant repository, dedicated to preserving and showcasing a wealth of historical and cultural artefacts.

The core mission of Saxony State Archaeology revolves around recording, presenting and safeguarding archaeological monuments. Excavations are only conducted when preservation is unfeasible, as they ultimately lead to the destruction of these valuable sites. In contemporary archaeology, modern scanning techniques hold a vital role in creating three-dimensional reconstructions of excavation areas and features, facilitating meticulous planning of archaeological sites, and significantly contributing to the digital documentation, preservation and protection of the archaeological findings.

Figure 1. Digitisation using the StereoScan neo with a turntable that allows access to every side of the artefact from a single scanner position.

Thomas Reuter, a dedicated surveyor working at the Archaeological Heritage Office Saxony (LfAS) since 2008, is mainly responsible for 3D documentation of findings. With advanced scanning techniques, he creates comprehensive and precise 3D models of artefacts and accurately documents their condition (what does the artefact look like or how it has changed over time). In addition to delivering essential support for scientific investigations within the office, Reuter also actively supports other offices and museums, especially regional or small museums that don’t want or cannot afford a high-resolution scanner for digitising their artefacts.

In archaeology, a significant challenge arises due to the absence of homogeneous materials suitable for digitisation and the lack of a standard set of items to measure consistently. The LfAS collection encompasses a vast and diverse array of artefacts, covering virtually everything imaginable that has been discovered throughout history. This wide spectrum of findings ranges from small discoveries like mouse vertebrae to extremely large objects, including several metre-long pieces of wood, as well as stones and gravestones that may weigh several tons. This variation encompassing not only size but also weight, poses challenges for transportation and technology enhancement.

Additionally, the materials’ surface characteristics add another layer of complexity to the digitisation process. Among them, matte ceramic surfaces stand out as the most preferred due to their ideal balance between darkness and lightness, facilitating quicker and more aesthetically pleasing scanning. Conversely, glazed stove tiles and partially glazed ceramics present greater difficulties during the scanning process.

Precious metals like gold, silver and bronze are often beautifully crafted, but their shiny surfaces and lustre can complicate accurate measurements. Wood also presents a unique challenge as it must be kept wet to prevent rapid decay and irreversible damage. This means that researchers must therefore also scan wet wood, carrying out their work while needing to strike a balance between ensuring the artefact remains moist without allowing standing puddles.

Initially, the artefacts’ images were preserved by employing a draughtsman to meticulously redraw them. To enhance efficiency and accuracy, LfAS later adopted a 3D laser scanner. However, with the retirement of the last draughtsman, LfAS decided to transition to advanced structured light scanning technology, which surpasses the limitations of the old laser method, such as noise behaviour or resolution deficits, thereby ensuring a more productive and complete approach to the application.

This advanced machine is predominantly used to scan small and delicate artefacts, including coins, coin fragments and jewellery pieces.

It has been used by LfAS with external DSLR cameras to map images that provide even better colour for texture mapping. In early 2023, LfAS further elevated their approach to digitising archaeological material to new heights with Hexagon’s cutting-edge structured light scanning technology in the form of the StereoScan neo.

The StereoScan neo uses Hexagon’s innovative Smart Phase Projection (SPP) technology, which employs a novel fringe projection pattern to yield the highest quality data on even the most difficult surfaces. In comparison to classic fringe projection patterns, SPP enables superior scanning of glossy and dark surfaces without taking the risk of adding additional matte coating spays or cleaning, which could potentially damage the original states of the artefacts.

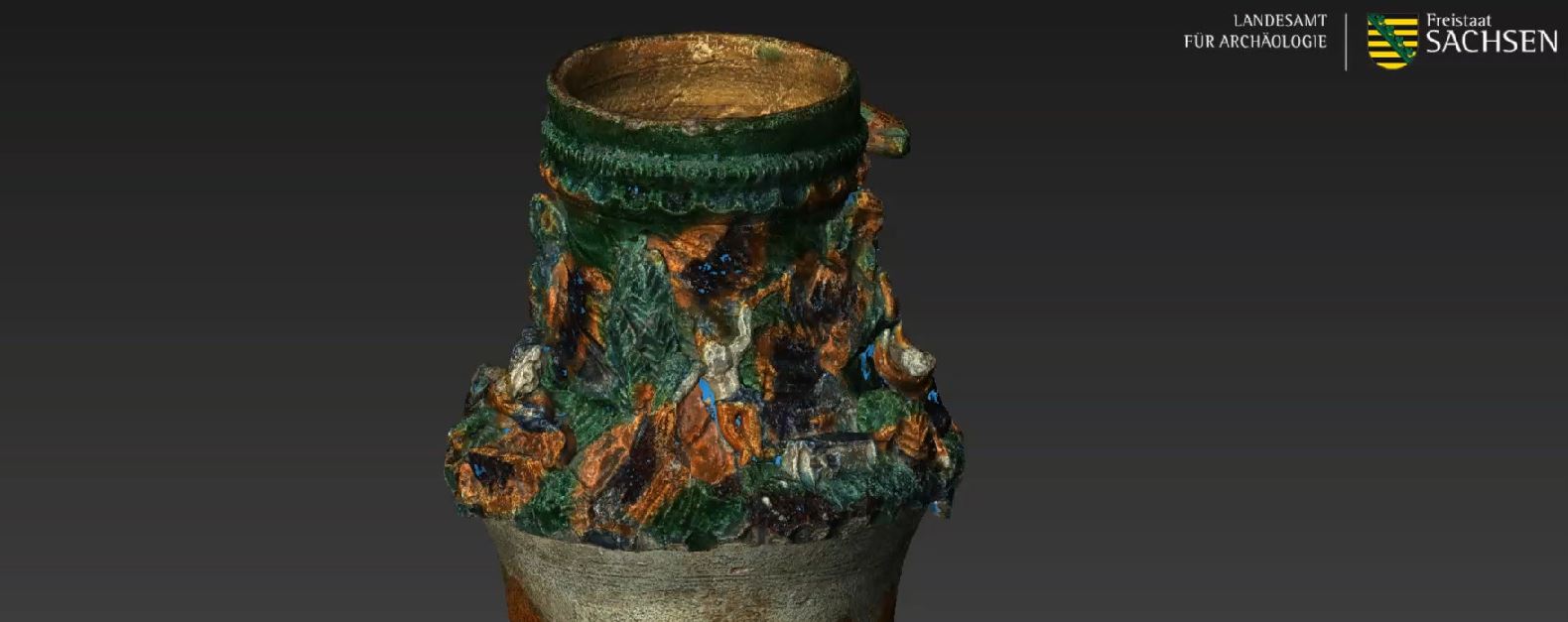

Figure 2. A close-up of the sophisticated surface of an artefact.

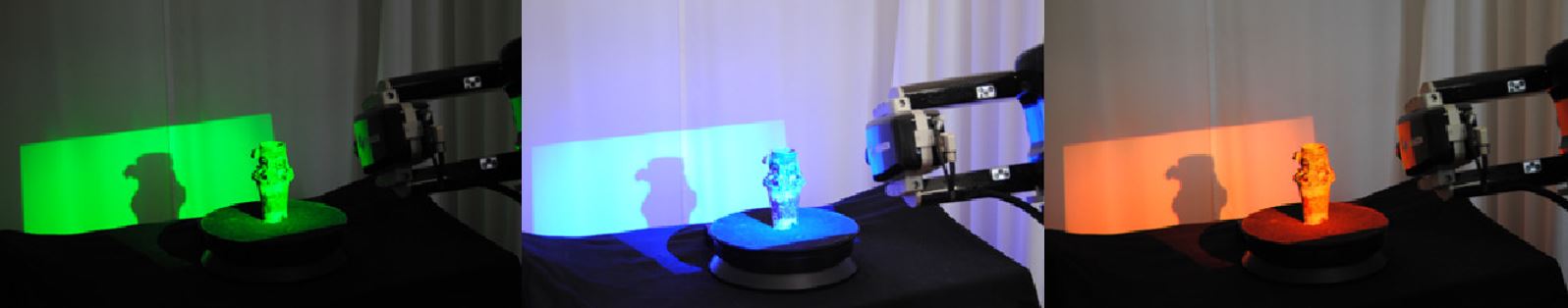

Figure 3. The StereoScan neo’s adaptive full-colour projection technique using strong illumination from three LEDs.

LfAS also equipped an automatic turntable connected to the device, streamlining the digitisation process and minimising physical contact — vital in this field. This automation significantly reduces the scanning time for each object. To ensure comprehensive scanning, each object undergoes scanning from six-to-eight directions. The data collected is automatically combined using OptoCat software for precise alignment.

The software aligns the scan data. Included in the merge process is overlapping data from multiple scans as well as data reduction and compression. Further post-processing steps include hole filling and texture mapping. OptoCat’s algorithm maps detailed bitmap information to each triangle of the scanned object with sub-pixel accuracy, using multiple pixels per triangle instead of just one colour per vertex. The texture resolution is separate from the object’s 3D data resolution, enabling the creation of a smaller point cloud while preserving a high-resolution texture.

The proper operation of both the equipment and software does not require the surveyors to have in-depth knowledge of photography. Even for those encountering this equipment and technology for the first time, such as the LfAS interns from Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (HTW) Dresden, it takes only a maximum of two weeks for them to operate the system independently and smoothly.

Figure 4: 3D model of the artifact

Figure 5. The texture mapping process for 3D scan data using Hexagon’s OptoCat software for structured light scanning systems.

Due to the varying sizes and weights of the pieces under examination, surveyors have to move, rotate, turn and set up for scanning from different directions to accommodate each object. To address this issue, LfAS equipped their laboratory with a FOBA A-600 mobile column stand.

Reuter attended training with the Hexagon team for the first time ten years ago. The training session left a profound impression on him as it involved transitioning from a laser scanner to a structured light scanner, rendering much of his previous knowledge unnecessary and requiring him to start almost from scratch. To set up the system for the first time, he spent a day with enthusiastic remote support from the Hexagon team through email and phone. With the StereoScan neo, he attended practical on-site training at the Hexagon Meersburg offices, and later combined it with online theoretical training to further enhance his expertise.

LfAS has been in the 3D documentary business for 18 years, successfully scanning around 25 000 objects in this time. Some of these scanned objects are now displayed and freely accessible at LfAS’s online museum, Archaeo 3D (archaeo3d.de). Moving forward, the experts at LfAS have ambitious plans to restore a heavily damaged collection, which suffered from bombings in 1945, by adopting a systematic approach that involves digitisation to make it accessible again. Additionally, they aim to use existing technology to provide further support to regional museums in Saxony, as well as engage in national and transnational projects.

Figure 6. The StereoScan neo powers LfAS’s 3D documentation journey.